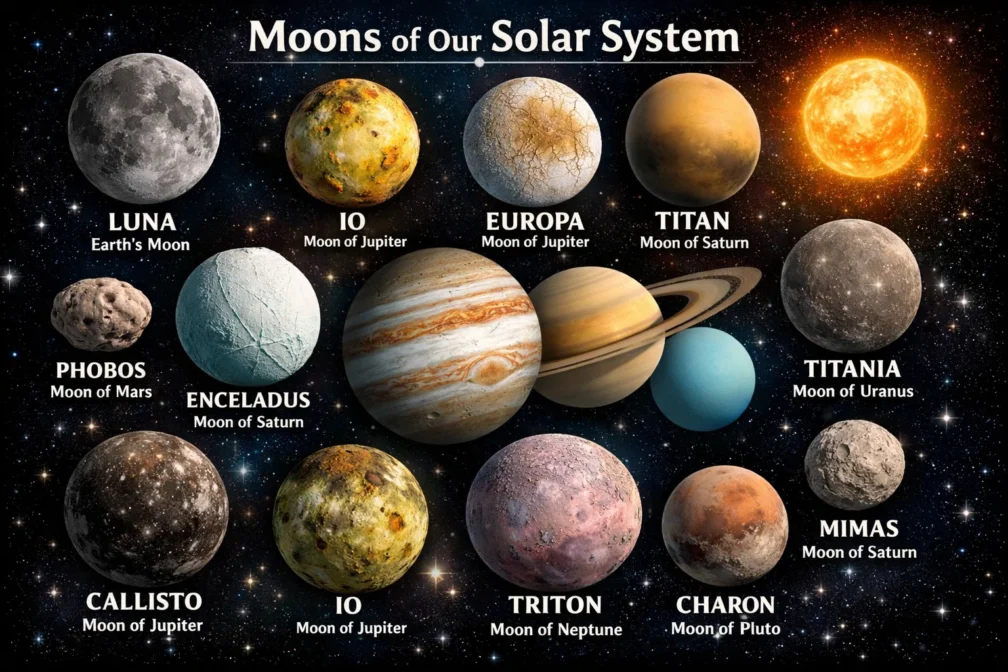

Look up at our own brilliant Moon, and it’s easy to think of it as a singular, quiet companion. But venture beyond our home planet, and you discover a reality far more spectacular. Our solar system is not merely a collection of planets orbiting the Sun; it is a vast arena teeming with worlds in their own right the moons. These are not just inert rocks drifting in the void. They are landscapes of unimaginable violence, hidden subsurface oceans that could cradle life, and atmospheric mysteries that challenge our understanding of chemistry and geology.

This comprehensive guide is a journey to these captivating satellites, offering a deep dive into their origins, their astonishing diversity, and their profound implications for one of humanity’s oldest questions: Are we alone? By exploring the moons of our solar system, we fundamentally explore the potential for life and the dynamic processes that shape worlds everywhere.

Defining a Moon in the Cosmic Context

A moon, or natural satellite, is traditionally defined as a celestial body that orbits a planet or a dwarf planet. This simple definition, however, belies an incredible complexity. These objects are bound by their host’s gravity, but they can rival or even surpass planets in size and intrigue. The formation stories of these moons are as varied as the moons themselves, primarily falling into three categories. Co-accretion suggests moons formed from the same swirling disk of gas and dust as their parent planet, much like a mini solar system. Giant impacts, like the one believed to have created Earth’s Moon, involve cataclysmic collisions that eject material into orbit. Capture proposes that a planet’s gravity can seize a passing object, locking it into a permanent dance.

Understanding these origins is crucial because it frames our exploration. It tells us why some moons are geologically dead while others are fervently active. It explains compositional similarities and stark differences. The study of the moons of our solar system is, in essence, archeology on a planetary scale. By examining their surfaces, interiors, and orbits, we read the violent and creative history of our entire cosmic neighborhood, uncovering chapters of collision, migration, and dynamical chaos that shaped the planetary system we see today.

Earth’s Moon: Our Familiar Benchmark

Our own Moon serves as the foundational reference point for all lunar science, a world we have visited and studied in intimate detail. It is a testament to a violent birth, formed from the debris of a collision between a young Earth and a Mars-sized body named Theia. This origin is etched into its composition and its lack of a significant atmosphere or magnetic field. Its surface, marked by dark volcanic plains (maria) and bright, cratered highlands, tells a story of ancient lava flows and a relentless bombardment that has slowed over billions of years. It is a largely geologically silent world, its internal heat long since dissipated.

Yet, the Moon’s silence is its scientific virtue. Its surface is a pristine historical record, largely uneroded by wind or water. The craters provide a relative chronology for the solar system’s early, chaotic era—a period called the Late Heavy Bombardment. Furthermore, it acts as a critical stepping stone for human exploration, a proving ground for technologies and life-support systems needed for deeper voyages. As we look to establish a sustained presence on the Moon, we are not just revisiting our past; we are using it as a platform to gaze further, toward the more enigmatic moons of the outer solar system that beckon with far stranger possibilities.

The Martian Moons: Captured Mysteries

Orbiting the Red Planet are two small, irregular moons—Phobos and Deimos—that resemble lumpy potatoes more than spherical worlds. Their appearance and orbital characteristics strongly suggest they are captured asteroids, inhabitants of the main belt between Mars and Jupiter that wandered too close and were snared by Martian gravity. Phobos, the larger and inner moon, is locked in a slow death spiral, gradually moving closer to Mars and destined to be torn apart by tidal forces in tens of millions of years. Deimos, farther out, is slowly drifting away.

These moons are of intense interest for both scientific and future mission support. Scientifically, they are thought to be pristine samples of asteroid-like material, potentially containing clues about the early building blocks of the solar system. For future human exploration of Mars, Phobos has been proposed as a potential initial base or a source of material. A outpost on Phobos could allow remote operation of Martian surface robots with minimal time delay, a concept known as telepresence. Studying these captured moons offers a convenient way to analyze asteroid composition without the challenge of landing on a small, fast-rotating body in the distant asteroid belt.

The Galilean Satellites: Jupiter’s Mini Solar System

When Galileo Galilei pointed his telescope at Jupiter in 1610, he discovered four points of light that changed our cosmic perspective forever. These Galilean moons—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—are planet-sized worlds that form a exquisite miniature solar system around the gas giant. Each is a masterpiece of extreme planetary science. Io, the innermost, is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, its surface constantly remade by hundreds of volcanoes powered by intense tidal heating from Jupiter’s gravity. Next is Europa, a smooth, icy globe hiding a global saltwater ocean beneath its frozen crust, making it one of the most promising places to search for extraterrestrial life.

The outer two Galilean moons are no less remarkable. Ganymede is the largest moon in the entire solar system, even bigger than the planet Mercury. It is the only moon known to generate its own intrinsic magnetic field, and evidence strongly suggests it, too, possesses a substantial subsurface ocean sandwiched between layers of ice. Callisto, the most distant of the four, is one of the most heavily cratered objects known, a fossil world whose ancient surface hints at conditions in the early Jovian system. Together, these four moons demonstrate how a single energy source—Jupiter’s gravity—can produce radically different evolutionary paths, creating a laboratory for comparative planetology right in our cosmic backyard. The dynamic processes observed on these key members of the moons of our solar system continue to reshape our theories of geology and habitability.

Saturn’s Crown Jewels: Titan and Enceladus

Saturn’s realm is dominated by two moons that have fundamentally altered astrobiology: the shrouded giant Titan and the icy geyser world Enceladus. Titan is a world strikingly similar to a primordial Earth, but with a fascinating twist. It is the only moon with a dense, substantial atmosphere—primarily nitrogen, like Earth’s, but laden with methane and complex organic chemistry. Its surface features stable liquid bodies, not of water, but of methane and ethane, forming rivers, lakes, and seas. This makes Titan the only other place in the solar system with an active liquid cycle akin to Earth’s hydrological cycle.

Enceladus, a small, bright moon, presents a different kind of wonder. Its south pole is marked by giant fissures known as “tiger stripes” that erupt colossal plumes of water vapor, ice grains, and organic molecules directly into space from a global subsurface ocean. Cassini spacecraft data confirmed this ocean is salty, possesses hydrothermal activity on its seabed, and contains all the basic ingredients thought necessary for life. While Titan offers a laboratory for prebiotic chemistry on a surface scale, Enceladus offers a direct sample of a potentially habitable ocean, easily accessible from orbit. These two moons together make Saturn’s system a primary target in the search for life beyond Earth, showcasing the incredible diversity found among the moons of our solar system.

The Medium Moons of Saturn: A Tapestry of Surprises

Beyond its two superstars, Saturn hosts a collection of mid-sized icy moons, each with a unique and bewildering personality. Iapetus presents one of the solar system’s great visual riddles: one hemisphere is as bright as snow, the other as dark as asphalt. The leading theory suggests dark material, possibly flung from the outer moon Phoebe, accumulates on Iapetus’s leading face, where it absorbs heat and triggers a runaway process of ice sublimation. Hyperion is a chaotic, sponge-like wreck of a world, tumbling unpredictably and filled with bizarre, deep pits with dark material at their bottoms.

Other Saturnian moons tell equally compelling stories. Mimas, with its staggering Herschel Crater, bears an uncanny resemblance to the “Death Star” from popular fiction, a testament to an impact that nearly shattered it. Tethys hosts a massive canyon system, Ithaca Chasma, which may be a fracture from an ancient, global freezing event. Rhea, the second-largest Saturnian moon, appears to be a largely dead, cratered world, but even it may have a tenuous ring system of its own, a claim that, if confirmed, would be a first. This menagerie illustrates that even without global oceans or thick atmospheres, the medium moons of our solar system are dynamic worlds shaped by impacts, tidal forces, and mysterious geological processes we are only beginning to decipher.

The Major Moons of Uranus: The Sideways Worlds

The Uranian system, aligned on its side due to a colossal ancient impact, holds five major moons—Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon. These are dark, icy worlds, their surfaces likely coated in a layer of dark, unprocessed organic material. Miranda, the innermost and smallest, is perhaps the most bizarre object of its size in the solar system. Its jumbled surface features giant fault canyons 12 times deeper than the Grand Canyon and three unique, coronae—trapezoidal regions of grooved terrain that suggest a violent past of shattering and re-accretion.

The larger Uranian moons show more familiar, yet complex, geologic histories. Ariel appears to be the youngest, with the fewest craters and extensive networks of fault valleys suggesting past tectonic activity, potentially driven by tidal heating. Umbriel is ancient and dark, its most prominent feature a bright ring on the floor of a crater named Wunda. Titania and Oberon, the largest, show hints of past endogenic activity, with Titania possessing enormous rift valleys and Oberon showing possible volcanic flows of a watery “magma” in its distant past. The exploration of these moons remains a major gap in planetary science, as only Voyager 2 has given us a fleeting glimpse, leaving their true natures as some of the most intriguing puzzles among the moons of our solar system.

Triton: Neptune’s Captured Oddity

Neptune’s largest moon, Triton, is an absolute rule-breaker. It orbits in a direction opposite to Neptune’s rotation (a retrograde orbit), the strongest evidence that it is a captured object, likely a former denizen of the Kuiper Belt. This capture event would have been extraordinarily violent, heating Triton’s interior and possibly leading to its fascinating surface we see today. Despite surface temperatures near absolute zero, Triton is geologically active. Voyager 2 observed geysers of dark, nitrogen-rich material erupting from its surface, driven by solar heating of subsurface volatile ices.

Triton’s surface is a complex patchwork of cantaloupe-like terrain (diapirs of rising ice), frozen nitrogen plains, and few impact craters, indicating a surface that is regularly renewed. Its thin atmosphere, primarily nitrogen with a hint of methane, is seasonal, varying as Triton’s poles take turns facing the Sun during its extreme seasonal cycle. As a likely captured Kuiper Belt Object, Triton serves as a gigantic, active preview of the kind of world the New Horizons spacecraft would later fly past at Pluto. It is a critical bridge in our understanding, showing that geological activity is not confined to the inner solar system or tidally heated moons, but can occur in the frozen reaches through unique mechanisms and a violent history.

Pluto’s System: A Complex Dance in the Kuiper Belt

Once considered the ninth planet, Pluto is now the king of the Kuiper Belt and the center of its own intricate lunar system. Its largest companion, Charon, is so massive that the pair orbit a barycenter located in the space between them, making them a true binary dwarf planet system. Charon’s surface shows a dark, reddish polar cap unofficially named Mordor, vast plains of frozen ammonia or water, and a tectonic belt of canyons that suggests a past global expansion, possibly from an internal ocean freezing.

Pluto’s four smaller moons—Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra—add further dynamical wonder. They orbit chaotically, tumbling unpredictably due to the complex gravitational interplay of the Pluto-Charon binary. Their bright surfaces suggest they are coated in relatively clean water ice. The entire Plutonian system is thought to be the product of a giant impact, much like Earth and its Moon, but on a smaller, icy scale. The New Horizons flyby revolutionized our view, revealing Pluto and Charon as complex, geologically active worlds with mountains of water ice, glaciers of nitrogen, and possible subsurface oceans, forever changing our perception of dwarf planets and their moons at the edge of the solar system.

Moons of Dwarf Planets and Small Bodies

The domain of moons extends far beyond the major planets. Numerous asteroids and dwarf planets boast their own satellites, providing key insights into formation and collisions. The dwarf planet Haumea has two moons, Hiʻiaka and Namaka, and is itself shaped like a football, all believed to be remnants of a gigantic collision. The dwarf planet Eris, which triggered the Pluto debate, has one moon, Dysnomia. Even some large asteroids in the main belt, like 87 Sylvia and 216 Kleopatra, have been found to possess moons, often nicknamed “moonlets.”

These systems are invaluable natural laboratories. By studying the orbits of these moons, scientists can precisely calculate the mass and density of the primary object, revealing its composition (whether it is rocky or a loose rubble pile). The presence and characteristics of these moons often tell a story of disruption. A grazing collision can chip off fragments that become moons, or a catastrophic impact can completely shatter a body, with the debris re-coalescing into a primary and one or more satellites. The study of these miniature systems helps us understand the frequency and effects of collisions, the building blocks of planet formation, and the dynamics of the early solar system, proving that lunar systems are a common feature across all scales of celestial bodies.

The Search for Habitability Beyond Earth

The most profound shift in planetary science in the last few decades is the realization that the traditional “habitable zone”—the region around a star where liquid water can exist on a surface—is not the only game in town. The discovery of subsurface oceans on moons like Europa, Enceladus, Ganymede, and possibly others has introduced the concept of “internal habitability.” Here, liquid water is maintained not by sunlight, but by internal heat generated from tidal friction or radioactive decay, protected from harsh surface radiation by a thick ice shell.

This expands the potential abodes for life astronomically. Worlds once considered frozen, dead orbs are now prime astrobiological targets. Enceladus’s plumes, which contain water, organics, and a chemical energy source (hydrogen gas), check all the boxes for a habitable environment. Europa’s chaotic terrain suggests interaction between its ocean and surface, and its ocean may have more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. As Dr. Robert Pappalardo, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, has noted, “The moons of the outer solar system have taught us that habitability isn’t just about distance from a star. It’s about having the right chemistry, energy, and liquid water, which can exist in surprising places.” This paradigm shift places icy moons at the forefront of humanity’s search for life.

The Engineering Challenge of Lunar Exploration

Venturing to these distant moons presents monumental engineering and logistical hurdles. Missions to the outer solar system require years of travel, sophisticated power sources like Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs), and incredibly robust autonomous systems. Landing on a moon like Europa or Enceladus adds layers of extreme complexity: penetrating thick ice shells, operating in high-radiation environments near Jupiter, and ensuring absolute planetary protection to prevent forward contamination of a potentially habitable ocean.

Proposed mission architectures are marvels of ingenuity. For Europa, NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission will conduct detailed reconnaissance from orbit. Future concepts include landers equipped with seismometers and compact melt probes, or even small submarines. For Enceladus, a simpler mission could fly directly through its plumes, analyzing the ejected material with advanced mass spectrometers. Titan, with its thick atmosphere, is ideal for aerial platforms like the planned Dragonfly rotorcraft, which will hop across the surface to study multiple locations. Each mission is a custom-designed solution to unlock the secrets of these unique worlds, pushing the boundaries of technology to answer fundamental scientific questions.

A Comparative Overview of Major Moons

The table below provides a structured overview of some of the most significant moons of our solar system, highlighting key attributes that define their scientific interest.

| Moon (Planet) | Key Feature & Significance | Potential for Habitability | Primary Exploration Missions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europa (Jupiter) | Global subsurface saltwater ocean under icy crust. Smooth, young surface with cracks and chaos terrain. | Very High. Ocean in contact with a rocky seafloor, likely chemically rich with energy sources. | Galileo, Juno (study’s Jupiter’s effects), Europa Clipper (upcoming). |

| Enceladus (Saturn) | Active water-vapor/ice geysers from a subsurface ocean, ejecting organics and salts into space. | Very High. Direct sampling of ocean material shows key ingredients (water, organics, energy, salts). | Cassini (discovered and analyzed plumes). Future plume-sampling missions proposed. |

| Titan (Saturn) | Dense nitrogen-methane atmosphere, liquid methane/ethane lakes & rivers, complex organic chemistry. | High (but exotic). Potential for prebiotic chemistry or even methane-based life in liquid hydrocarbons. | Cassini-Huygens (lander), Dragonfly (rotorcraft, upcoming). |

| Ganymede (Jupiter) | Largest moon, only one with its own magnetic field. Likely a subsurface ocean between layers of ice. | Moderate/High. A vast, deep ocean, but may be trapped between ice layers without direct rock contact. | Galileo, Juno, JUICE (ESA mission, upcoming). |

| Io (Jupiter) | Most volcanically active body; surface covered in sulfurous volcanoes and lava lakes. | None. Extreme radiation and volcanic surface. Scientific interest in tidal heating and extreme geology. | Voyager, Galileo, Juno. |

| Triton (Neptune) | Captured Kuiper Belt Object with active nitrogen geysers and a young, complex surface. | Speculative. Past tidal heating may have created a subsurface ocean; current activity is fascinating. | Voyager 2 (only flyby). |

| Charon (Pluto) | Binary companion to Pluto; canyons, smooth plains, and dark polar cap suggest complex history. | Low. Possible past subsurface ocean, now frozen. Key for understanding binary system formation. | New Horizons (flyby). |

The Future of Lunar Discovery and Exploration

The next two decades promise a golden age in the study of solar system moons. Major missions are already on the books: NASA’s Europa Clipper will perform dozens of close flybys of Europa to assess its ocean and ice shell. ESA’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) will focus on Ganymede but also study Callisto and Europa. NASA’s Dragonfly mission will send a rotorcraft to soar through Titan’s atmosphere, landing at multiple sites to study its prebiotic chemistry. These flagship missions will generate terabytes of data, transforming hypotheses into concrete knowledge.

Looking further ahead, concepts abound. Enceladus is a prime target for a dedicated life-finding mission, perhaps one that lands near its tiger stripes or samples its plumes more comprehensively. Advanced cryobots capable of melting through kilometers of ice to reach Europa’s or Enceladus’s oceans are in early development. There is also a growing push to return to the Uranian and Neptunian systems with orbiters, as their moons represent a vast, unexplored frontier. Each of these endeavors is driven by the fundamental truth uncovered in the last generation: the moons of our solar system are not mere accessories to planets. They are central characters in the solar system’s story and arguably our best hope for discovering a second genesis of life.

Conclusion

From the familiar silence of our own Moon to the erupting plumes of Enceladus and the methane rivers of Titan, the moons of our solar system present a staggering panorama of worlds. They defy simple categorization, hosting oceans of water and hydrocarbons, atmospheres thick and thin, and geological processes of unimaginable scale and variety. This journey through the lunar realms of each planet reveals a solar system far more dynamic, diverse, and promising than we dreamed just a half-century ago.

These are not mere points of light in a telescope; they are destinations. They hold the keys to understanding planetary formation, the ubiquity of habitable environments, and perhaps, one day, the existence of life beyond Earth. Our exploration has only just begun, and as we look to the future, it is clear that the story of our solar system will be increasingly written not just by its planets, but by its magnificent, captivating moons.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many moons are in our solar system?

The official count is constantly rising as telescope technology improves and we discover smaller and fainter objects orbiting planets and dwarf planets. As of now, the total number of confirmed moons in our solar system exceeds 290, with Jupiter and Saturn having the most at over 90 each. This number includes everything from planet-sized bodies like Ganymede to tiny, irregular moonlets only a few kilometers across.

Which moon is most likely to support life?

Europa and Enceladus are currently tied as the top candidates. Both have strong evidence for global subsurface saltwater oceans in contact with a rocky seafloor, providing water, chemistry, and potential energy sources. Enceladus has the advantage of actively ejecting its ocean material into space, where we have already detected organic molecules. Europa has a much larger ocean. Titan, with its liquid methane cycle and complex organics, represents a completely different, exotic possibility for life.

What is the largest moon in the solar system?

Jupiter’s moon Ganymede holds the title of the largest moon in our solar system. With a diameter of about 5,268 kilometers (3,273 miles), it is larger than the planet Mercury and would be classified as a planet if it orbited the Sun directly. It is also the only moon known to generate its own magnetic field.

Can a moon have its own moons (a submoon)?

Theoretically, yes, and the term for such an object is a “moonmoon” or submoon. However, stable orbits for submoons are likely very rare. The gravitational influence of the much larger parent planet tends to destabilize the orbit of a submoon, either causing it to crash into the primary moon or be ejected. No confirmed submoons have been discovered in our solar system to date.

Why do we study moons instead of just planets?

Moons offer unique and varied laboratories that planets sometimes cannot. They exhibit extreme geological processes driven by tidal forces (like on Io), reveal pristine records of the solar system’s bombardment history (like on our Moon), and provide accessible environments to search for liquid water and life beyond the traditional habitable zone (like on Europa and Enceladus). Studying the moons of our solar system gives us a much broader and more complete understanding of planetary science, formation, and the potential for life in the cosmos.